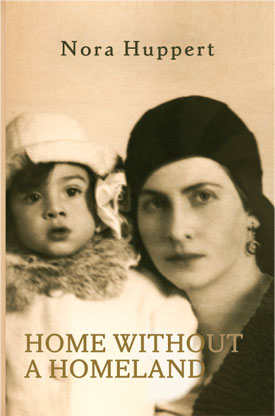

Home without a homeland

Nora Huppert

Sydney Jewish Museum, 2012

Buy from the Bookshop at the Museum,

148 Darlinghurst Rd, Darlinghurst 2010

phone (02) 9360 7999

or any Gleebooks shop; phone main branch on (02) 9660 2333

Thank you, Diana, for your care, support and encouragement throughout this project. Your confidence, good humour and optimism went a long way to helping me reach this result. I would never have achieved it without you. Nora Huppert

READ REVIEWS

|

|

|

Nora Huppert, Home without a homeland, extracts

In Berlin

‘When [my father] was a boy there was an obsession among the power-brokers with building a strong German Navy. In 1902, as part of the endless Latin lessons, the Gymnasium’s Director hammered home how essential a strong fleet had been in the Roman Empire’s defeat of its enemies. When the Minister needed funds for his dreams of maritime dominance, schools were set the task of assisting. Papa’s Gymnasium was directed to raise enough to build a battle cruiser.

“My father was aghast,” he wrote in his memoir. “As I presented the collection box to him, he told me: ‘I donate nothing for Kaiser Wilhelm’s floating coffins!’" When Papa repeated the patriotic arguments he had been taught in school, my grandfather continued: “That’s all nonsense. England will not attack us, nor our colonies—which cost far more than they’re worth. A Navy will only undermine our good relationship with England, reinforce their suspicions about the Kaiser’s policies, and isolate us politically.”

Papa disagreed. The following Sunday he took to the streets with his collection box. “The passers-by were by no means as patriotic as I had expected. ‘What sort of a Navy? Spare me some Groschen to get rid of this beggar,’ they grumbled.” He hurried on to the Palace Hotel in Potsdamer Platz, and found the guests there more forthcoming. “Silver coins soon rattled in my collection tin.”

“My shyness had all but vanished by the time I knocked on another door. I stood transfixed on the threshold by six Chinese, in splendid silk robes, sporting gold-rimmed spectacles, with hair in pigtails down their backs. I had surprised them at their breakfast.”

Of course, he had never before seen Chinese people.

“‘What do you want, little one?’ they asked kindly.

‘Please may I have a contribution towards building the Navy?’”

“They invited me to step inside and inspected my collection box, which indicated its purpose with the signature of Admiral Tirpitz. One of the gentlemen interpreted. Then they all broke into smiles. I caught sight of their fingernails—longer than the ones in the Struwelpeter story.”

They began to question Papa, asking him against which enemy his fleet would make war. “Against England! Director Kuebler has declared that England must be destroyed.”

“The Chinese smiled some more, and the senior man had his silk purse handed to him, from which he extracted a gold coin, twenty marks in gold, which he dropped into my tin.”’

(from My father from Berlin)

In the English countryside during World War II, with the McNairs

‘The kitchen was always warm and busy, especially on Fridays, and I recall one particular day when Mum Mac, who suffered from rheumatism and was often in pain, was seated in her customary spot at the kitchen table, surrounded by well-used scales, bowls and baking dishes. Lilly and Mrs Keep were also in their usual places at the other end of the table. The weekly silver cleaning was in progress and all the silver cutlery, finely crafted jugs, ornamental covers for meat dishes, big and small bowls and platters were spread out for cleaning.

It was morning-tea time and lured by the sweet smell of baking I joined the women and found a stool by the stove. I liked to feel its warmth, since much of the time I was cold in this big draughty house. Yet when I was asked I would firmly deny it, since that might have seemed impolite. Above all, I wanted to fit in and never offend anyone, especially the adults. Brownie lay under the table, alert but with his eyes closed. I was not used to animals in the house and I was still ill-at-ease with them.

I looked around the big kitchen. The oak table around which we sat was scrubbed every Friday and had stood on its solid legs for several generations. It could comfortably seat four on either side and two at each end. There was a space between it and the largest wooden dresser I had ever seen, big enough for a pram to pass through. The dresser stretched from floor to ceiling. The lowest shelf held the family’s black Wellington boots and leather shoes, all cleaned by the housemaid. Above were capacious drawers for the ironing blanket and sheet used every Friday. If the electricity failed, heavy older irons were heated up on the Rayburn solid fuel stove.

I listened to the women’s chatter around me and hoped to be invited to participate. I had learned quickly that children only spoke when spoken to. Most of the talk was about whose son, brother or husband had been called up, or had sent a letter or card, or where the fighting was, and how far Hitler’s army had advanced or been repelled.

I knew that the other drawers of the dresser contained clean laundry waiting for ironing, and odds-and-ends such as wrapping paper, twine for the garden and packets of seeds. The papers, The News Chronicle, The Farmers’ Weekly, The Kentish Times and Picture Post , together with local maps and current War-zones were piled on a shelf. Above them were stored cups and crockery for daily use. The rest of the alcove was piled with dog baskets, cat cushions, a coal scuttle and logs for the fire.

That day I felt pleased when Mrs Keep addressed me, and I replied quite animatedly. Then I realised that the others had ceased their chatter and were all looking at me. I was embarrassed and wondered if I had done something wrong. Mum Mac slowly rose to her feet and painfully came towards me. Her rheumatism must have been really bad that day. As she approached, I experienced a vivid flashback: That’s exactly how my Nazi teachers used to look when coming to hit me. I averted my eyes in preparation for the blow. Gently Mum Mac took my small hands in her large work-worn ones and said kindly and quietly, as was her way: “In this country, Nora dear, we do not talk with our hands.”

For many years thereafter my hands remained firmly at my side when I spoke, lifeless, and often inexplicably cold.’

(from Wartime schooldays)

In post-War London

‘As well as his other impressive attributes, Brook possessed a motor car. He was the first of my boyfriends to own such a luxury. It had wide soft brown leather upholstered seats, running boards (wonderfully helpful with stiletto heels) and indicators that clicked in and out and occasionally became stuck. It was painted a dashing racing green. The outside windscreen wipers, operated from above, clicked back and forth, and also occasionally became stuck so that the windscreen fogged over. Night driving in the rain in dimly-lit London was a particularly hazardous adventure. Brook’s car was an old pre-War Morris or Ford, and lived in a tiny shed by the river. It required great skill to manoeuvre it into this tight space which barely allowed a door to be opened.

Since there was little opportunity for regular outings, the faithful machine was often difficult to start, needing strong encouragement from the crank handle in the front. Petrol was still in short supply, but Brook always had enough to get us to some friendly pub or restaurant by the Thames, where I would sip a glass of sherry. I developed a taste for the sweet Spanish variety. Brook would tell me funny Army stories, spellbinding at the time, but soon forgotten. Eventually I had my first full sexual experience in the back of that car. I thought it a bit messy and wondered if that was all there was to it.

What followed, however, was much more significant. My military hero began to tell me riveting stories of a very different nature. I learned of the horrors of General Monty’s North African campaign, its heat and noise, the enemy planes constantly overhead, the slaughter of comrades, the stealthy night manoeuvres, the utter fatigue, and the misunderstood commands received and passed on. All this painted a very different picture from what I had watched in the romanticised heroic films at the local cinemas during the War. I didn’t know it then, but Brook was traumatised by his experiences. At times he would lie sweating and shaking in my tired arms, as he relived incidents and experiences too dreadful to forget. I listened in silence as the full horror of what he had gone through began to sink in.’

(From classroom to cutting room)

|