|

|

|

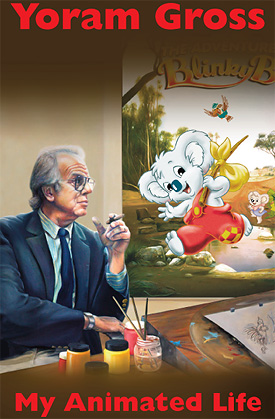

Read extracts, My Animated Life

‘On Sundays only, white bread made our dreary lives more bearable, and it tasted better with butter, so I would buy fifty grams at the market. A rather stout woman there would assure me that the butter was fresh: she had brought it herself from the country. She would carefully weigh this little bit of butter and wrap it in clean white paper. This in itself caused a problem. Of the fifty grams at least twenty soaked into the paper, and this was a considerable loss for people like us, with little money to spare.

This state of poverty led to our setting up our ceramics industry. In order not to waste the butter I bought a little unglazed dish, probably meant as a salt dish.

Natan approved of this purchase, and because he possessed artistic talent, decided to decorate the dish in imitation of the Goldscheider ceramics produced in Vienna. He remembered the flower vases from our father’s shop. They were very beautiful and we had some of them at home.

When painted, the salt dish looked most attractive, and because I had some talent for business, I proposed that we should invest ten zlotys and buy three flower vases for Natan to decorate in the same style as our butter dish. We would then try and sell them at a profit.

As the elder brother, Natan would normally not accept my ideas, which I admit were not always wise. This time, however, he thought the proposal was good and worth trying. Our investment was not very large. I bought the vases and the paint and Natan was pleased, because the painting of these "baby potties" as I called them, allowed him to express his artistic soul.

With the three decorated vases nicely wrapped, I went by tram to look for a china shop. My first client was a smallish shop in Marszalkowska Street.

"Well, all right, young man, show me these pots you have for sale," said my first client, a middle-aged man with a rich moustache. I placed the three vases before him. There was no one else in the shop, which pleased me, because the gentleman with the moustache, probably the owner, had all the time he needed to look at my "wares". He muttered something which I could not understand, smoothed his moustache, then said: "Wait!" He went into a back room, returning after a minute with his wife. "What do you think, Kasia? He wants ten zlotys a piece and said these were hand-painted by Franciszek Grymek, one of the most famous Warsaw artists."

The wife picked up a vase, looked at it from every angle, and said at last: "Ask Andrzej."

"Andrzej, come here," called out the husband and a young fellow, perhaps twenty years old and obviously the couple’s son, came out looking rather sleepy.

"Look, Andrzej, Franciszek Grymek painted these himself."

"And who is this Grymek?" asked the son.

"How would I know?" said the mother. "I only know that one –what’s his name again? uh, Robert Bertrand." Probably Mrs Kasia meant to say "Rembrandt". "But it’s not dear– he only wants ten zlotys each," she stressed.

Andrzej picked up one of the vases and sniffed it. "Fresh paint– likely stolen," he said.

"What is this nonsense?" I said in a raised voice. "You don’t have to buy–but don’t tell me I’m a thief!"

"All right, all right," Andrzej tried to pacify me. "Buy one, Daddy, and we’ll see how it sells."

I took the ten zlotys, so recouping our initial investment.’

(From Chapter 11)

‘The War had already taught me all kinds of tricks, and it did not take me long to work out how to lead a group of friends who wished to leave Poland with neither passports nor visas out of the country. I asked my tall friend Igo also to buy himself a military uniform so he could pretend to be my aide. The others I instructed to pack just the minimum necessities and dress very modestly, since they were to act the part of prisoners. My assignment was to escort them to Germany.

"Please don’t hand-cuff us," begged Doda. Of course I did not, for I did not have any hand-cuffs, and my "prisoners" in any case behaved themselves well when escorted by me and my "aide". In his kit bag he carried six bottles of vodka.

I had no side-arm but I think I created the right impression by occasionally shouting at my prisoners, telling them not to straggle, but to march as they had for hard labour during the War. There was a small difference: during the War the Nazi guards were armed with revolvers, and would fire these off every now and then either to frighten us or to kill anyone who was walking too slowly because he was exhausted.

We reached the railway station and enquired when the next train for Germany would leave. Natan’s saying, "The stupid have all the luck" also applied this time. A train for Germany was leaving within the hour. Unfortunately, all the carriages were already full and it was impossible to push on our group of eight. There was no way we could be separated– after all, the prisoners might run away! I ordered them to squat on the platform next to the train, with my aide guarding them. Then with a quick and determined step I approached one of the carriages, energetically threw open the door, and loudly ordered: "Everybody out! Immediately and at the double!"

I don’t know where all this energy and invention came from, but apparently I created the image of a tough officer, because the passengers did begin to leave the carriage, if not very fast. "Hurry. Hurry!" I shouted. Soon there was not a single person left. Using the same commanding tone, I ordered my group: "Get in, two by two– and no talking! Do as I tell you, understand? Haben sie verstanden?" I wanted my prisoners to appear to be Germans I was escorting to prison, and I must admit they behaved accordingly, showing sad and frightened faces.

The train did not start "within the hour", as the guard had told us it would. After a two-hour wait the engine whistled and we were off. Since we had the carriage to ourselves, my friends were able to tell me that they were very impressed with how well I performed as an "officer". The War had taught me to play various roles, not often on stage, but always before people who believed that I was indeed whoever I was pretending to be.

We travelled for several hours, well pleased that we were moving in the right direction and that nobody disturbed us. Every time the train stopped at a country station, someone would try to enter our carriage. I would immediately shout: "No one’s allowed in here with the prisoners!" Of course no one wanted to travel with criminals.’

(From Chapter 23)

|